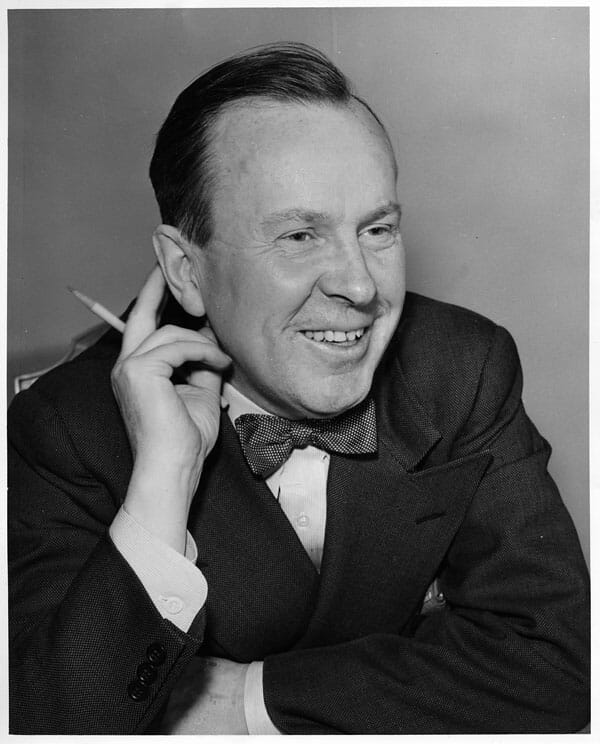

On his birthday, let’s celebrate Lester B. Pearson’s contribution to Canada’s place in the world

April 23, 2013

Canada’s rise as an important middle power and active and influential diplomatic player is best symbolized by a historic vote at the United Nations General Assembly in October of 1956. On that day the UN decided to create an emergency force to supervise the withdrawal of Israeli, British and French troops from Egyptian territory and to ensure the maintenance of a cease-fire agreement. UNEF, as it was called, soon became known as “the blue berets” – soldiers working under the flag not of their own country, but of the United Nations itself.

The Canadian diplomat and politician front and centre on this day in New York was Lester Pearson, a man whose intelligence, charm and personal skills put together a resolution of a conflict that threatened the peace of the region and the world. Pearson’s personal contribution received its due recognition when he won the Nobel Peace Prize that December. Today, on his birthday, it is appropriate to remember his invaluable contribution to Canada’s place in the world – a place now threatened by a government for which foreign engagement is unimportant and which has replaced action with rhetoric; helpfulness with provocation and taking sides.

In 1953, Gamal Abdul Nasser’s decision to nationalize the Suez Canal electrified the Egyptian people with its boldness. But for others, particularly the British and the French, it seemed an echo of Hitler. Israel, whose very existence Nasser saw as an affront to Arab pride and sovereignty, was alarmed for its own reasons. At a series of secret meetings the three countries agreed to engineer an attack by Israel on Egypt, to which the British and French would respond by sending in their own troops to “protect” the Canal.

The outbreak of violence was met with shock and harsh opposition around the world even among allies. What had seemed to the Israelis, the French and the British to be a brilliant manoeuvre turned overnight into a major political embarrassment.

Louis St Laurent, the Canadian Prime Minister, was outraged at what he saw as an act of deep folly and illegality. He encouraged Pearson to do everything possible to avert a deeper crisis. Canada’s Foreign Minister was uniquely placed to do just that. Widely respected in Washington and London, Pearson was equally well known in the corridors of the United Nations. And he was ably assisted by a group of young Canadians diplomats who were committed to building a peaceful world governed by rules.

Pearson shrewdly saw the idea of a peacekeeping force as accomplishing two objectives – building the credibility of the UN and getting the Suez invaders off the hook. But he also had to persuade the Egyptians to allow for foreign troops on their soil, something that Nasser reluctantly allowed only if it was done under the UN flag, and could at any time be removed unilaterally by him. Eleven years later Nasser insisted that the troops leave, an ominous precursor to the Six Day War.

When the General Assembly passed the resolution that established the UN Emergency Force, the delegates surrounded the Canadian desk, offering congratulations to Pearson and his team. Canada was at the centre of the action, constructive, engaged and effective. It was a good day.

Bob Rae

Liberal Foreign Affairs critic